FACTS OF THE CASE

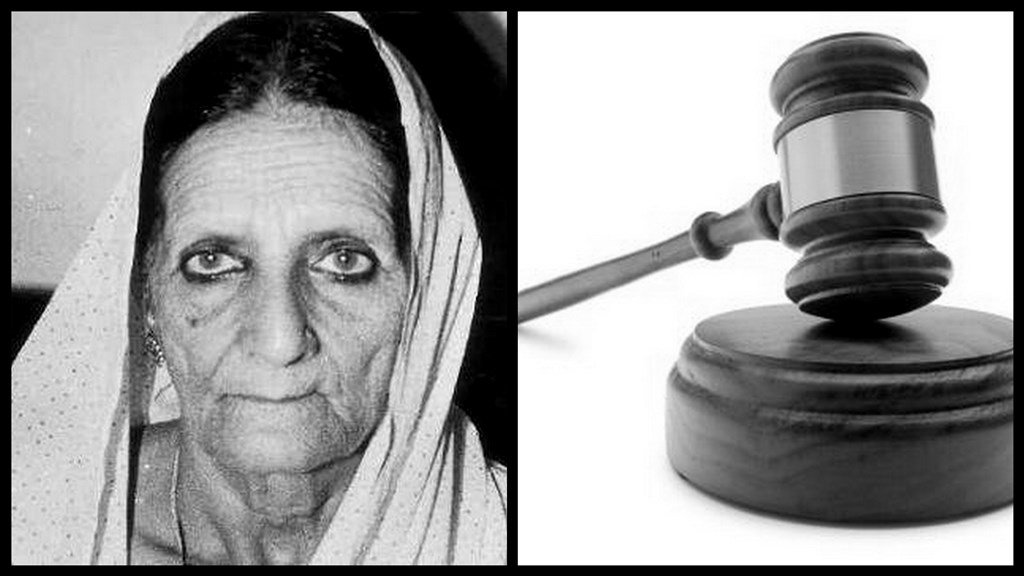

The Shah Bano case was a landmark case in India that involved the issue of maintenance for divorced Muslim women. In 1978, Shah Bano, a 62-year-old Muslim woman from Indore, Madhya Pradesh, was divorced by her husband, Mohammed Ahmed Khan, after 43 years of marriage. Khan had refused to pay maintenance to Bano after the divorce, which led her to approach the court for relief.

In 1985, the Supreme Court of India, in a historic judgment, granted maintenance to Shah Bano under Section 125 of the Criminal Procedure Code, which provides for maintenance to be paid to wives, children, and parents who are unable to maintain themselves. The court ruled that Shah Bano was entitled to maintenance from her former husband even after the divorce.

The court observed that the Muslim Personal Law, which governed matters of marriage, divorce, and inheritance for Muslims in India, was discriminatory against women and violated the Constitution of India’s principles of equality and justice. The court noted that while Muslim men were allowed to divorce their wives by pronouncing the word “talaq” three times, Muslim women had no such right, and were often left destitute after divorce.

The judgment was met with strong opposition from conservative Muslim leaders, who saw it as interference in their religious affairs. The Indian government, led by Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi, faced pressure from both Muslim and Hindu groups to overturn the judgment.

In response to the controversy, the government passed the Muslim Women (Protection of Rights on Divorce) Act in 1986, which nullified the Supreme Court’s judgment and limited the maintenance payable to divorced Muslim women to a period of three months after the divorce. The Act was widely criticized for going against the principles of gender justice and equality enshrined in the Constitution.

Opinion of Supreme Court

In its judgment in the Shah Bano case, the Supreme Court of India held that Shah Bano was entitled to maintenance from her former husband under Section 125 of the Criminal Procedure Code, even after the divorce. The court observed that the Muslim Personal Law was discriminatory against women and violated the principles of equality and justice enshrined in the Constitution. The court also noted that Muslim women did not have the right to divorce their husbands in the same way that Muslim men did, which often left them destitute after divorce. The Supreme Court’s decision was seen as a landmark judgment for women’s rights in India and was widely praised by women’s groups and progressive sections of society. However, the judgment was also met with strong opposition from conservative Muslim leaders, who saw it as interference in their religious affairs. The government subsequently passed the Muslim Women (Protection of Rights on Divorce) Act, which nullified the Supreme Court’s judgment, and limited the maintenance payable to divorced Muslim women to a period of three months after the divorce.

Movement against the judgment

The Supreme Court’s judgment in the Shah Bano case was met with strong opposition from conservative Muslim leaders and groups, who saw it as interference in their religious affairs. They argued that the Muslim Personal Law, which governed matters of marriage, divorce, and inheritance for Muslims in India, was based on Islamic principles and should not be subject to scrutiny by civil courts.

There were widespread protests and demonstrations against the judgment by conservative Muslim groups, who argued that the court’s decision went against the tenets of Islam and threatened to undermine the traditional social structure of Muslim society. Some Muslim organizations even issued fatwas (religious edicts) against the judgment, calling for a boycott of the courts and the legal system.

The opposition to the judgment was also fueled by political considerations, with various political parties and leaders seeking to exploit the issue for their own purposes. The ruling Congress party, led by Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi, was under pressure from both Muslim and Hindu groups to overturn the judgment. In response, the government passed the Muslim Women (Protection of Rights on Divorce) Act, which nullified the Supreme Court’s judgment and limited the maintenance payable to divorced Muslim women to a period of three months after the divorce.

The government’s decision to overturn the judgment was widely criticized by women’s groups and progressive sections of society, who saw it as a setback for women’s rights and a betrayal of the principles of gender justice and equality enshrined in the Constitution. The Shah Bano case thus became a symbol of the ongoing struggle for women’s rights in India and the tensions between religious law and civil law in the country.

Dilution of the effect of the judgment

The effect of the Supreme Court’s judgment in the Shah Bano case was diluted by the subsequent passage of the Muslim Women (Protection of Rights on Divorce) Act, which nullified the court’s decision and limited the maintenance payable to divorced Muslim women to a period of three months after the divorce. The Act was widely criticized for going against the principles of gender justice and equality enshrined in the Constitution, and for undermining the rights of Muslim women.

The Act was seen as a political compromise aimed at appeasing conservative Muslim leaders and groups, who had opposed the court’s decision and threatened to disrupt social harmony. The Act effectively overruled the Supreme Court’s judgment and reinforced the primacy of the Muslim Personal Law in matters of divorce and maintenance.

The Act was also criticized for failing to address the larger issue of gender discrimination in the Muslim Personal Law and for perpetuating the unequal treatment of women under the law. The Shah Bano case thus highlighted the need for comprehensive legal reforms to ensure the equal rights of Muslim women and to bring the Muslim Personal Law in line with the principles of gender justice and equality enshrined in the Constitution.

Reactions to the act

The Muslim Women (Protection of Rights on Divorce) Act, which was passed by the Indian Parliament in 1986, was met with mixed reactions from various sections of society. The Act was seen as a political compromise aimed at appeasing conservative Muslim leaders and groups, who had opposed the Supreme Court’s decision in the Shah Bano case and threatened to disrupt social harmony.

Conservative Muslim leaders and groups welcomed the passage of the Act, which they saw as a victory for Islamic principles and a reaffirmation of the primacy of the Muslim Personal Law in matters of divorce and maintenance. They argued that the Act had corrected the Supreme Court’s error in interfering with religious matters and had restored the traditional social order of Muslim society.

However, the Act was criticized by women’s groups and progressive sections of society, who saw it as a betrayal of the principles of gender justice and equality enshrined in the Constitution. They argued that the Act had diluted the effect of the Supreme Court’s judgment in the Shah Bano case and had perpetuated the unequal treatment of women under the law.

Critics of the Act also pointed out that it had failed to address the larger issue of gender discrimination in the Muslim Personal Law and had only provided limited protection to divorced Muslim women. They called for comprehensive legal reforms to ensure the equal rights of Muslim women and to bring the Muslim Personal Law in line with the principles of gender justice and equality enshrined in the Constitution.

Later Developments

The Shah Bano case and the subsequent passage of the Muslim Women (Protection of Rights on Divorce) Act continued to be the subject of intense debate and controversy in India. Over the years, there have been various developments in the legal and social sphere that have impacted the rights of Muslim women.

In 2001, the Supreme Court of India passed a landmark judgment in the Danial Latifi case, which upheld the right of Muslim women to seek maintenance from their husbands even after the divorce, under Section 125 of the Criminal Procedure Code. The court observed that the Muslim Personal Law was not a “law” under Article 13 of the Constitution and that the principles of gender justice and equality enshrined in the Constitution applied to all citizens, regardless of their religion.

In 2017, the Supreme Court passed another landmark judgment in the Shayara Bano case, which declared the practice of instant triple talaq (talaq-e-biddat) unconstitutional and violative of the principles of gender justice and equality enshrined in the Constitution. The court observed that the practice of instant triple talaq had no basis in Islamic law and was arbitrary, unfair, and discriminatory against Muslim women.

These judgments were seen as significant victories for women’s rights in India and were widely welcomed by women’s groups and progressive sections of society. However, there is still a long way to go in terms of ensuring the equal rights of Muslim women and bringing the Muslim Personal Law in line with the principles of gender justice and equality enshrined in the Constitution. The issue continues to be a subject of intense debate and discussion in India.

Challenge to the validity of the Act

The Muslim Women (Protection of Rights on Divorce) Act, which was passed by the Indian Parliament in 1986, was challenged in the Supreme Court of India in the case of Sarla Mudgal v. Union of India. The petitioners argued that the Act was unconstitutional and violated the principles of gender justice and equality enshrined in the Constitution.

The Supreme Court, in its judgment in the Sarla Mudgal case, upheld the validity of the Act, but observed that it did not provide adequate protection to divorced Muslim women and was discriminatory against them. The court called for a comprehensive review of the Muslim Personal Law to ensure the equal rights of Muslim women and to bring it in line with the principles of gender justice and equality enshrined in the Constitution.

In subsequent years, there have been several other petitions filed in various courts challenging the validity of the Act and seeking greater protection for the rights of Muslim women. In 2015, the Supreme Court admitted a petition filed by the Bharatiya Muslim Mahila Andolan seeking a declaration that the Muslim Personal Law was unconstitutional and violative of the fundamental rights of Muslim women.

However, the court has not yet passed a final judgment on the petition, and the issue continues to be a subject of intense debate and discussion in India. The challenges to the validity of the Act highlight the need for comprehensive legal reforms to ensure the equal rights of Muslim women and to bring the Muslim Personal Law in line with the principles of gender justice and equality enshrined in the Constitution.